from the editor's desk

A Review of Sylvia Martin’s ‘Ink in her Veins: The Troubled Life of Aileen Palmer

Sylvia Martin. Ink in her Veins: The Troubled Life of Aileen Palmer. Crawley, Western Australia: UWA Publishing. RRP: $29.99, 350 pp, ISBN: 9781742588254.

Nathan Hobby

Aileen Palmer (1915-1988) was an Australian poet and communist activist. After serving in the Spanish Civil War and in war-time London, she spent much of the second half of her life in psychiatric institutions. Sylvia Martin’s new biography of Palmer reveals, unsurprisingly, a woman who lived in the shadow of her parents, Nettie and Vance Palmer, Australia’s literary power-couple of the first half of the twentieth century. Toward the end of the biography, Martin quotes the verdict of David Martin (presumably no relation) on Palmer’s life: ‘Her attempt to write from within the Palmer constellation, her failure to escape. Chain-smoking her life away in Sunbury mental hospital, felled by her sexuality. Aileen was the poet’ (246). Sylvia Martin’s accomplished biography largely confirms this verdict while adding the important dimension of her political activism and war service.

Ink in her Veins divides Palmer’s life into three sections, putting the weight on Palmer’s childhood and war years. In ‘Part I: A Promising Life’, Martin reconstructs Palmer’s childhood using the extensive papers of Nettie and Vance and Palmer’s many semi-autobiographical writings. Martin’s narration of Nettie and Vance’s early lives up to Palmer’s birth strategically emphasises aspects to set up Palmer’s story, including Vance’s institutionalised brother, Wob. After Aileen’s birth, Nettie put aside her poetry: ‘I don’t want ink to run in Aileen’s veins,’ she proclaimed, with what could be seen with hindsight as prophetic irony’ (35). Despite holding this sentiment at the time, Nettie and Vance expected their two daughters would become writers, while being uneasy with much of what Palmer would write, especially when it was about them or seemed connected to her mental illness. The portrait of the Palmers’ family life and literary world is a rich one, peopled with writers like Katharine Susannah Prichard (a mentor to Palmer) and Henry Handel Richardson. (A quibble—Martin has Nettie only knowing Prichard slightly in 1914 from Prichard’s attendance at university evening classes in 1906 [31-32]. However, according to Prichard’s autobiography, Prichard and Palmer—along with Christian Jollie Smith—became friends while they were all still at school through Prichard’s neighbour and best friend, Hilda Bull [63].) After writing prodigiously and precociously as a child, Palmer completed a first-class honours degree at the University of Melbourne while becoming a fully-fledged communist, unlike her more moderately left-wing parents.

‘Part II: A Decade of War’ narrates Aileen’s fateful years caught up in two wars. The whole family was in Spain when the Civil War broke out in 1936; they fled to London but Palmer insisted on returning to serve the Republican cause against the fascists. Her hospital service near the front line with the British Medical Aid Unit is an important story but, described in detail, it can’t help but assume a little of the monotony of war itself. Devastated by the Republican loss, Palmer moved to London and served with the Auxiliary Ambulance Service during the Second World War, a harrowing job. It was while in London that Palmer had relationships with two unnamed women. With some convincing sleuthing, Martin offers a plausible solution to the identity of one of them, but only after the scenes in which she’s appeared and without any further information on her. Despite the fulfilment Palmer tenuously enjoyed in this period, Martin concludes that ‘sadly… she does not appear to have had any more relationships in life after her return to Australia in her early thirties’ (210).

‘Part III – A Life in Fragments’ covers, in just sixty-four pages, the rest of Palmer’s life from her unhappy return to Melbourne in 1945 to her death in a psychiatric nursing home in Ballarat in 1988. Appropriately, these chapters are far shorter than the rest of the book as the biography itself gives the sense of fragmenting. Living with her aging parents and haunted by the war, Palmer was drinking heavily and suffering a manic phase when the family forced her into a mental hospital for the first time in 1948. She was to live the rest of her life in and out of institutions, only managing to find temporary, low-skilled jobs. However, in 1962 she achieved a measure of fame with her ‘translation’ of Ho Chi Minh’s Prison Diary in 1962—turning a literal English translation into a more poetic version—and in 1964 a collection of her poetry was published, World Without Strangers?. It’s in this final section that Martin’s comment in the introduction that Palmer is ‘[t]antalising, yet always just out of reach,’ rings most true (3). Given her struggle to emerge from her parents’ shadow, it’s ironic that she does not fully achieve it even in a biography devoted to her, with her life after the death of Nettie in 1964 (Vance had died in 1959) covered in just two short chapters. The glimpses Martin offers of Palmer’s institutional life are intriguing, leaving me to wonder if they could have been expanded on. However, there may be a lack of sources, as well as the challenge of representing less public, less event-driven phases of a life, a problem for biographers identified by Susan Tridgell (119).

Sylvia Martin makes a welcome appearance in her preface, describing how she became intrigued with Nettie and Vance’s ‘tragic daughter’ and something of how she ‘followed a biographer’s trail, within Australia and across the world’ (3). By convention, biographers are usually restricted to appearing in the introduction or afterword, but Martin briefly re-appears at points throughout this biography to confide her uncertainty, or process of discovery, such as in this instance: ‘The further I went into exploring and decoding what appeared at first to be largely delusional raving, the more ‘sense’ I found in this richly allusive text’ (228). I like the way these kind of appearances by biographers illuminate the biographical process, but perhaps in this book there aren’t quite enough of them to achieve a critical mass and set up the right expectations for readers, rather than jolting them each time.

Palmer’s semi-autobiographical writings pose a biographical challenge. So, for example, an unpublished novel, ‘Poor Child!’, offers a vivid depiction of Palmer’s final years at Presbyterian Ladies’ College and first year at Melbourne University. Many incidents in the novel are corroborated in real life by entries in Nettie’s diaries, yet ‘in this novel Aileen starts her lifelong practice of renaming people and places in her semi-autobiographical writing. Melbourne becomes, evocatively, Helbourne’ (80). Some critics would urge greater caution than Martin shows in using works like this as biographical sources, but I believe she achieves the right balance. Chapter six is called ‘Poor Child!’ and it sums up the novel and its picture of these years, suggesting parallels to Palmer’s life while not often pressing them. Bringing in a second semi-autobiographical novel based on the papers of another in Palmer’s circle, Martin confesses, ‘Sometimes I have felt that working on Aileen Palmer’s autobiographical writing, in which actual people and places are given fictional names (and not always the same ones), is a little like entering a hall of mirrors, where nothing is quite what it seems’ (91).

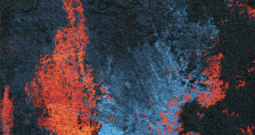

It’s a beautifully presented book, well designed with a striking and complex cover picture of Palmer. Some of the style choices are notable. Out of all the sources, the words of Aileen Palmer alone are italicised. It’s an effective technique, her voice standing out from the rest of the text and running like a thread through the biography. The body of the book is stripped of citations, the referencing contained at the back with short quotes followed by the source. This adds to the sense of the work as a narrative and it may make the book more accessible to the general reader—but, perhaps naively, I like to imagine the general reader can handle and even benefit from footnotes or endnotes, as well as it improving the scholarly utility.

Paradoxically, Palmer’s literary obscurity widens the potential audience for Ink in her Veins. It isn’t a biography just for readers who know the writer’s work. Nor is it primarily a biography arguing for her posthumous recognition as a major writer, even though it finds much to value in her work. Instead, the biography’s purpose is to recover a significant story: that of Palmer’s troubled life as a writer who was also a woman in under-recognised military service, a closeted lesbian in a time of intolerance, and a mental patient in a time of stigma and institutionalisation. The biography stands on its own as the compelling story of an unusual and important life, a story worth recovering and well told.

Works Cited

Prichard, Katharine Susannah. Child of the Hurricane: An Autobiography. Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1963. Print.

Tridgell, Susan. “Biography, Narrative and Christina Stead: An Imperfect Match?” Journal of Australian Studies 28.83 (2004): 117–126. Print.

Nathan Hobby won the T.A.G. Hungerford Award for his novel, The Fur, and is writing a biography of the early life of Katherine Susannah Prichard as a PhD candidate at UWA. He blogs at nathanhobby.wordpress.com.